What is affirmative action?

In the US, young whites are far more likely to get a bachelor's degree than young blacks and Hispanics:

Affirmative action refers to policies that give students from underrepresented minority groups a boost in the college or university admissions process. The term affirmative action can also refer to policies that boost minority prospects in employment or contracting, but this cardstack will focus on race-based affirmative action in US higher education.

Rationales: Supporters cite three main reasons affirmative action policies are helpful or necessary.

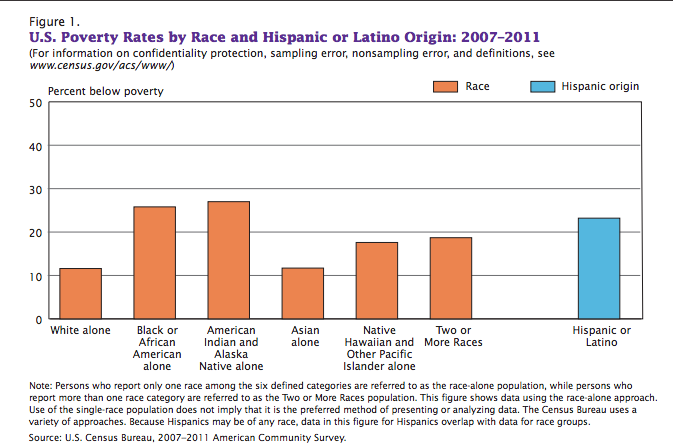

- Discrimination, past or current: Racial discrimination, particularly against African-Americans but also other racial groups, has been a constant through most of American history. Affirmative action is often seen as a way to help fight discrimination that is still pervasive today, or to improve the disadvantaged position of some groups that is the consequence of centuries of past discrimination.

- Lack of opportunities: Even in the absence of deliberate discrimination, many members of minority groups may simply have fewer opportunities available to them. They may be less prepared for the SAT or the college admissions process in general because of where they grow up, where they went to school, etc. Affirmative action programs are meant to ensure these students don't miss out on opportunities.

- Diversity and representation: Finally, some supporters argue that, regardless of the reasons, it's simply neither just nor wise to have racial minorities severely underrepresented at universities, as has frequently been the result in states where affirmative action is banned. In this line of thinking, ensuring representation is valuable in itself. Many also maintain that affirmative action benefits universities by ensuring that people from different backgrounds get to contribute. Colleges argue that affirmative action benefits everyone on campus, because students are better off if they're exposed to a more diverse educational environment.

How it works: In the US, public colleges and universities — and private colleges receiving federal funding, which is virtually all — have to be very careful about how they use race in their admissions processes. They are only allowed to consider race as one of many factors in weighing an application. They aren't allowed to create a racial quota (reserving, say, 10 percent of spots for a certain group) or to use a standardized racial bonus (giving 20 extra points to each minority applicant); both of these approaches have been ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, in the Regents v. Bakke and Gratz v. Bollinger cases.

Still, the overall effect is to admit more students from underrepresented minorities, even though many have lower test scores than other admitted applicants. Of course, that happens in other contexts, too: colleges often admit certain students despite lower-than-average test scores — say, athletes, or children of wealthy alumni.

The controversy: There are several common criticisms of the use of affirmative action in university admissions. Most prominently, opponents argue that the programs themselves are racially discriminatory, since they favor certain racial groups and not others. Several white students have sued universities, arguing that their scores would have qualified them for admission if not for affirmative action programs. And some argue that the programs can hurt Asian-Americans, restricting their admissions opportunities in elite schools despite high test scores.

Others argue that affirmative action programs currently help many members of minority groups who are already wealthy or well-connected, and don't need a boost, and that the programs should help disadvantaged people of all races instead. Finally, some critics maintain that these programs may have unintended consequences, and hurt the people they're intended to help, by dropping them into academic situations they're not prepared for.

Is affirmative action popular?

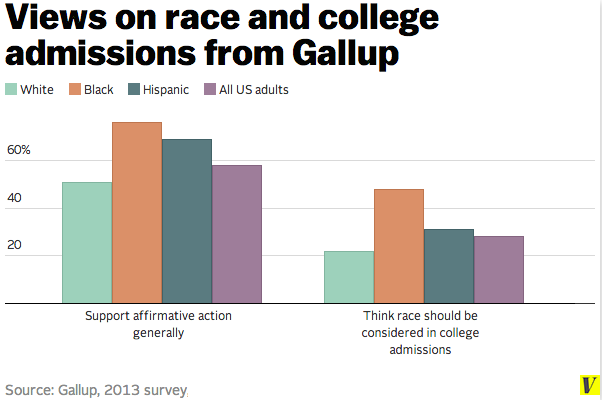

It depends on how you word the question. Generally, Americans don't seem to mind the idea of giving racial minorities a leg up, but their opinion changes if they're told those students aren't as academically qualified.

Gallup asked in 2013 whether "students should be admitted solely on the basis of merit, even if that results in few minority students being admitted" or "an applicant's background should be considered to help promote diversity on college campuses, even if that means admitting some minority students who would not otherwise be admitted."

A strong majority — 67 percent — opposed the consideration of race in college admissions when the question was phrased that way. Whites were the least likely to favor it, but a majority of Hispanics also said students should be admitted based solely on merit. Although a higher proportion of Democrats favored affirmative action than Republicans or Independents, a majority of respondents from all parties opposed it, Gallup found.

But the same Gallup poll found that Americans don't necessarily the concept of affirmative action; 58 percent said they generally favor "affirmative action programs for racial minorities," including a slim majority (51 percent) of whites.

The Pew Research Center asked the college admissions question in a different way in 2014: "In general, do you think affirmative action programs designed to increase the number of black and minority students on college campuses are a good thing or a bad thing?"

Nearly two-thirds of respondents — 63 percent — said they thought affirmative action described that way was a good thing, including 55 percent of whites, 80 percent of Hispanics and 84 percent of black respondents.

One sociologist has found that the definition of merit in college admissions could be changing for white people feeling threatened by Asian-American students' success. White Americans are more likely to support taking intangible quantities like leadership into account, rather than just grades and test scores, given a prompt that notes the high proportion of students of Asian descent at the University of California at Berkeley.

Are there alternatives to race-based affirmative action?

Affirmative action based on economic circumstances — giving poor students a boost, regardless of their skin color — is often suggested as a replacement for race-based affirmative action in college admissions.

Class-based affirmative action is sometimes seen as simply an end run around bans on racial preferences. In states that bar race-based affirmative action, colleges can turn to class as an alternative. Since black and Latino families are more likely to be poor than white families are, class can serve as a proxy for race, a way to make sure that colleges have racial diversity even if they can't take race into consideration outright. (The two aren't mutually exclusive; colleges can give preferences to students based both on race and family income.)

But others see it as a superior system, not an inferior proxy. One argument for class-based affirmative action could be termed the Malia Obama argument. If colleges think about diversity solely in terms of race, President Obama's daughters will get an edge in college admissions that white children who grew up in poverty will not. (Obama has said he doesn't think that would be fair.) Wealthy students are already vastly overrepresented at colleges, particularly selective colleges. In 2006, just 5 percent of students at selective colleges came from the bottom income quartile, says Anthony Carnavale, director of the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce.

There are a few critiques of class-based affirmative action, particularly if it's used as the only form of affirmative action.

First, some argue that it isn't as effective at creating racial diversity as race-based affirmative action is. Others argue that the legacy of racial discrimination is weightier than the challenges low-income students have accessing higher education. Black students were systematically shut out of higher education; poor students were not. There is also still a pervasive wealth gap between black and Latino families and white ones, even at high incomes. Class-based affirmative action can encourage stereotyping, critics argue, if the only students of color on campus are poor.

The best comparison of the effects of considering class versus race so far was at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Colorado came close to banning affirmative action in 2008, although the initiative ultimately failed; before the vote, though, the university had already developed a race-neutral plan to take students' incomes into account. Researchers found that underrepresented minority students were more likely to be admitted under class-based affirmative action than they were under race-based policies: admission rates were 9 percentage points higher for underrepresented minorities. For students from disadvantaged backgrounds of all races, admission rates were 20 percentage points higher under class-based affirmative action.

Does affirmative action harm Asian-American students?

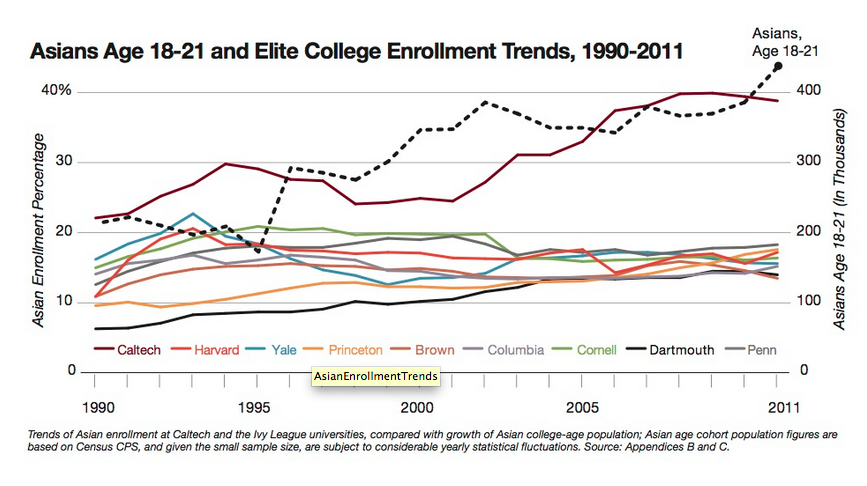

Many high-achieving students from Asian backgrounds believe that they're discriminated against in college admissions and that colleges often set de facto quotas for Asian students when they take race into account in admissions.

There is some evidence that Asian-American students' chances for admission are harmed by affirmative action programs. In 2005, a study from two Princeton University researchers found that without affirmative action, the admission rate for black and Latino college applicants would fall sharply. But white students would be largely unaffected — students of Asian descent would be the beneficiaries, getting about 80 percent of the slots no longer filled by other students of color.

At colleges where affirmative action is banned or race is not taken into account, there is a much higher proportion of Asian-American students within the student body; at the University of California at Berkeley, for example, Asian-American students make up 39 percent of the student body — more than double their share of the state population.

On the other hand, even as the share of college-aged Americans who are Asian has grown nationally, the proportion of Asian students at Ivy League colleges has remained flat, The American Conservative found in a review of demographic data. Ivy League colleges practice affirmative action; the California Institute of Technology, also a private college, focuses almost solely on academic achievement among applicants, and its Asian enrollment more closely tracks national population trends (while black and Hispanic students are underrepresented).

Source: The American Conservative

Because of this, some Asian-American groups oppose affirmative action. Organized Asian-American opposition was key to defeating an attempt to reinstate affirmative action in California in 2014.

But opinion is not monolithic among Asian-Americans, nor are all Asian-American students academic achievers from professional backgrounds. Some Asian-American subgroups have higher poverty rates than Americans as a whole and Cambodian, Laotian and Hmong-Americans have among the lowest college attendance rates in the country.

What does the Supreme Court say about the constitutionality of affirmative action?

The first Supreme Court decision on affirmative action, Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, was decided in 1978. It held that strict racial quotas should not be used in college and university admissions, but that affirmative action could be constitutional in some circumstances if race was considered as just one of many factors. In the 35 years since Bakke, this has remained the court's basic approach to affirmative action.

The court reopened the issue 25 years after Bakke, in Grutter v. Bollinger. In that 5-4 decision, the court ruled that colleges could take race into account as one factor in a holistic review when admitting applicants. The court found that the educational benefits of diversity were a compelling reason to create a diverse student body, but that affirmative action programs would need to be "narrowly tailored" — essentially decided on a student-by-student basis. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, writing for the majority, said she expected the Grutter decision to stand for 25 years.

It's important to note that neither case was a complete victory for the university involved, and both upheld the principle of affirmative action in theory while rolling it back in practice. In Bakke, the University of California's quota system was thrown out; in Gratz v. Bollinger, a case rolled into the Grutter decision, the University of Michigan law school was forbidden to use a point system that awarded additional points to applicants if they were from underrepresented minorities. In the 25 years between the two landmark cases, the court's rationale for allowing affirmative action shifted, from remedying past racial discrimination in Bakke to benefiting the entire student body in Grutter.

Two more recent cases have also weighed in on affirmative action. Schuette v. BAMN, decided in April 2014, sprung from the Grutter case; Michigan voters banned affirmative action by ballot initiative with a 58 percent majority not long after the Supreme Court decision. The court found those bans are constitutional, which could spur similar efforts in other states and left state bans elsewhere in place.

The most direct challenge to the precedents set in Bakke and Grutter, though, was Fisher v. Texas, a lawsuit over the University of Texas's consideration of race in admissions. The University of Texas at Austin admits most of its students by letting in students from the top 10 percent of every high school class. For other slots in the freshman class, it considers a range of factors — including race. Abigail Fisher, a Texas resident who didn't make the 10 percent cutoff and wasn't admitted using other criteria, sued, arguing her rights were violated.

In a 7-1 decision in 2013, the Supreme Court sent the Fisher case back to a court of appeals for further review. The lower court hadn't used a strict enough standard when evaluating Texas' affirmative action plan, the justices argued. The case returned to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, where it was reargued in November 2013. In July 2014, a panel of three justices again upheld Texas's affirmative action policy.

What are the effects of affirmative action?

The majority of colleges and universities in the US take everyone, or nearly everyone, who applies. So the debate about affirmative action is usually confined to a smaller universe of prestigious colleges and law schools. It is especially contentious because research has found that attending a highly selective college is more likely to affect lifetime earnings for students from low-income or minority backgrounds than for white, upper middle class students. So the stakes are high.

In a 1998 book on affirmative action, The Shape of the River, two former Ivy League university presidents — Derek Bok, the former president of Harvard, and William Bowen, the former president of Princeton — argued that affirmative action benefits both the individual students admitted under the policies and the campus as a whole. They compared white and black students who graduated in 1976 and 1989 from 28 prestigious public and private colleges. They found that black students who benefited from affirmative action generally succeeded despite their lower test scores; they graduated and went on to have successful lives, earning an average of $71,000 by their mid-30s and demonstrating high levels of civic participation.

However, some researchers continue to argue that, particularly in law school, affirmative action is harmful to students' later careers. This is an idea that researchers describe as "mismatch": graduates helped by affirmative action might struggle at schools or jobs that are too tough for them. Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas is an adherent of mismatch theory and uses it to argue that affirmative action actually harms minority students.

One of the more prominent debates in this area surrounded a 2004 Stanford Law Review article by UCLA law professor Richard Sander, about the effects of affirmative action on law students' post-graduation prospects.

Focusing solely on black and white law school students from 1994-96, he found that 88 percent of accredited law school grads passed the bar on the first try, and that 95 percent passed eventually. However, the pass rates for blacks were substantially lower: 61.4 for first-timers and 77.6 percent after five tries. Because affirmative action hurts black students by putting some in schools where they won't perform as well, Sander argued, it lowers the number of them that pass the bar. Eliminating race-based preferences, he calculated, would have boosted the number of black students who passed the bar among 2001 matriculants by 7.9 percent.

However, there are plenty of detractors to Sander's arguments. One Yale law student, Daniel Ho, wrote in response that Sander performed his analysis incorrectly and failed to prove that affirmative action at law schools causes lower bar-passage rates. Another pair of law school professors found that getting rid of affirmative action would decrease the number of black lawyers by 12.7 percent.

Other research has cast doubt on the mismatch theory, at least as it applies to undergraduate students. A study at the University of California found that students who had just made the admissions cutoff — those most likely to be mismatched — earned slightly lower grades than other students, but the difference disappeared when they were compared only to students with a similar educational background. While California doesn't have affirmative action, the study suggests that students with lower grades and test scores still benefit from attending a selective college.

Which states ban affirmative action now?

Besides Michigan, seven states currently ban affirmative action in public college admissions.

Most of these bans were passed directly by the voters and not by the state legislature.

What is the effect of a state ban on affirmative action?

A study in 2013 from the American Educational Research Association found that the bans work as intended: they eliminate the edge that underrepresented minorities have in college admissions, and the effect even spreads to neighboring states.

In some states with bans, the proportion of black and Hispanic freshmen at state flagship colleges and universities declined. Before California banned affirmative action in 1998, the proportion of black college freshmen at the University of California-Berkeley and the University of California-Los Angeles was about the same as the proportion of black college-aged students in the state.

After the affirmative action ban was passed, though, the proportion of black students on campus declined, the New York Times found in an examination of the data. Black students are 9 percent of the state's college-aged population, but only 2 percent of the student body at Berkeley.

Other states have seen different effects. In Florida, black students are underrepresented at state colleges and universities; while Hispanic students are still underrepresented, too, they haven't lost any ground since affirmative action was banned.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62291101/184696038.0.1542056890.0.jpg)